American Family Physician, 2015 Antalgic Gait Flow Sheet

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Gait characteristics associated with the pes and talocrural joint in inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 16, Commodity number:134 (2015) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Gait analysis is increasingly beingness used to characterise dysfunction of the lower limb and pes in people with inflammatory arthritis (IA). The aim of the systematic review was to evaluate the spatiotemporal, foot and talocrural joint kinematic, kinetic, peak plantar force per unit area and muscle activeness parameters between patients with inflammatory arthritis and healthy controls.

Methods

An electronic literature search was performed on Medline, CINAHL, SportsDiscus and The Cochrane Library. Methodological quality was assessed using a modified Quality Index. Effect sizes with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as the standardised mean difference (SMD). Meta-analysis was conducted if studies were homogenous.

Results

Thirty six studies with quality ranging from loftier to low met the inclusion criteria. The majority of studies reported gait parameters in Rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The gait pattern in RA was characterised by decreased walking speed (SMD 95 % CI −1.57, −2.25 to −0.89), decreased cadence (SMD −0.97, −i.49 to −0.45), decreased footstep length (SMD −1.66, −one.84 to −1.49), decreased talocrural joint power (SMD −1.36, −1.70 to −1.02), increased double limb support fourth dimension (SMD ane.03, 0.84 to 1.22), and peak plantar pressures at the forefoot (SMD 1.11, 0.76 to 1.45). Walking velocity was reduced in psoriatic arthritis and gout with no differences in ankylosing spondylitis. No studies have been conducted in polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic sclerosis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Conclusions

The review identified the majority of studies reporting gait adaptations in RA, only express evidence relating to other IA atmospheric condition. Poor data reporting, small sample sizes and heterogeneity beyond IA conditions limit the interpretation of the findings. Future studies may consider a standardised analytical approach to gait assay that volition provide clinicians and researchers with objective testify of foot function in people with IA.

Groundwork

The term 'inflammatory arthritis' (IA) has been used to describe a number of inflammatory articulation diseases including: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and gout [i]. RA is a chronic progressive autoimmune disease characterized by joint swelling, joint tenderness and destruction of synovial joints [two]. SpA encompasses a heterogeneous grouping of inflammatory arthritic weather, characterised past vertebral involvement, peripheral oligoarthritis or polyarthritis, enthesitis, Every bit, PsA and undifferentiated spondyloenthesoarthritis [iii, 4]. Gout is a mutual grade of inflammatory arthritis caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals within joints and other soft tissue associated with hyperuricaemia [v]. IA causes lower limb and foot pain and damage, functional disability, reduced mobility, articulation deformity and altered gait strategy [6–10]. Human foot pain is considered an important factor in the development of antalgic gait in IA, specifically in RA and gout [6, eleven, 12]. In RA, foot hurting is derived from structural and functional alterations associated with inflammatory and structural change [6, 13]. With the development of an antalgic gait, adaptations occur based upon a hurting avoidance strategy. Previous studies have reported gait adaptations in RA and these include: a decrease in walking velocity and subsequent alterations to velocity related spatiotemporal parameters including, reduced cadence, increased double limb support time and decreased step length [xiv–18]. Changes to kinematic parameters including, reduced sagittal plane talocrural joint ROM and increased peak rearfoot eversion have also been reported [7, 14, 17, eighteen]. Furthermore, previous studies take reported amending to kinetic parameters including, reduced superlative ankle plantarflexor ability associated with reduced walking velocity, reduced ankle articulation ROM, reduced ankle articulation angular velocity, reduced ankle plantarflexor moments and decreased strength of the talocrural joint plantarflexor muscles [xvi, 17, 19]. An increase in peak forefoot plantar pressure parameters has also been reported in RA [16].

Gait analysis provides information about spatial-temporal parameters, kinetics, kinematics and muscle activity to farther delineate the relationship between joint disease, articulation impairments and compensatory gait strategies adopted to overcome painful and disabling deformities [xv, twenty]. Gait analysis has been reported as a useful clinical tool to quantify pes function in both early and established RA [7, 8, 14, 15]. Notwithstanding, less mutual IA weather condition, such as AS, PsA, gout, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, also have diverse consequences for the lower limb such as changes in human foot function, and extra articular complications involving the pare and vascular integrity [9, ten, 12, 21–24]. A recent systematic review of studies investigating walking abnormalities associated with RA, Baan [25] identified changes in gait such every bit a slower walking, longer double support time, and avoidance of extreme positions. These changes were in relation to the frequently establish static features in RA, for example, hallux valgus, foot planovalgus and rearfoot abnormalities. However, Baan [25] only reported gait parameters in RA and did non consider other IA weather. However, recently there has been an interest in evaluating gait patterns in other IA weather condition that includes gout [12], PsA [21] and AS [10]. No previous systematic review has conducted meta-analysis of gait parameters in IA compared to healthy command population. The aim of the systematic review was to evaluate spatiotemporal, foot and ankle kinematic, kinetic, peak plantar pressure and muscle activity parameters in people with IA and healthy controls.

Methods

Identification of studies

Four electronic databases were searched (Medline, CINAHL, SportsDiscus and The Cochrane Library). The search was completed in March 2015. The search strategy combined terms appropriate to the anatomical location; the type of gait analysis and IA condition (Additional file 1: Table S1). An initial review was undertaken of all titles and abstracts. All articles considered advisable were read in full to establish if they met the eligibility criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they: reported people with IA that included; RA, Every bit, PsA, gout, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus; if they assessed adults aged >18 years one-time; if they reported spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, peak plantar pressure or muscle activeness data during gait; if they were manufactures that included a healthy group as means of comparison. Only articles published in English were included. Surgical and pharmacological intervention studies were excluded. No limitation was placed on the date of the publication with databases screened up to March 2015.

Data extraction

All titles and abstracts identified through database searches were downloaded into Endnote X4 (Thomson, Reuters, Carlsbad, CA). Each title and abstract was evaluated for potential inclusion by two contained reviewers (MC, KR). If there was insufficient information contained in the championship to determine suitability the full text was obtained. Any discrepancies between the ii reviewers (MC, KR) were resolved at a consensus meeting.

Cess of methodological quality and diversity

The quality of studies was evaluated independently by two reviewers (MC and KR), who were blinded to author and publication details. Study quality was rated using a modified version of the Quality Index (QI) tool originally described by Downs and Black [26]. The QI tool consists of 27 items which allow for the cess of internal and external validity, reporting of bias and ability. The tool was modified to exclude thirteen questions that were not relevant to the articles assessed in this review, resulting in the retention of 14 questions. The scoring organization grades each of the 14 questions either a (0 = no/unable to determine, or 1 = yes) with the exception of question five (0 = no, i = partially, 2 = yes). The summed score for each report was calculated, the maximum doable being 15. No cut off scores have been described to categorise study quality for the Downs and Black quality Index [27]. In the absence of validated cut off scores and following review of past articles that have applied the Downs and Blackness criteria the follow cut off values were applied: ≥ 12 was considered high quality, ≥ seven but < 12 as moderate quality, and < vi every bit poor quality [27, 28].

Data assay and synthesis

Relevant gait parameters and information regarding overall study design, subject characteristics and gait analysis parameters were extracted from each paper by one author (MC) from those studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Data was tabulated according to the specific IA status and gait parameters.

The clinical and methodological diversity amid the studies was assessed to determine the appropriateness of data pooling for meta-analysis. Factors considered important for comparison included: hateful age, sexual practice distribution, instance and comparison group size, data conquering methodology and instrumentation. Two authors (MC and PP) reviewed the included studies and reached consensus on the appropriateness of conducting meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was considered low if the Iii value was ≤ 25 %, moderate if the value was > 25 % and ≤ 50 %, high if > l % and ≤ 75 % and very high if greater than 75 % [29]. A fixed-issue model was practical where the I2 statistic was less than l % and the Chi2 test indicated a non-pregnant degree of heterogeneity (P > 0.1). The random-effect model was used where the I2 statistic was greater than 50 % and the Chiii test indicated statistically pregnant heterogeneity (P < 0.1) [30].

Where data was available from each paper a standardised mean divergence (SMD) (Hedges'due south yard) and 95 % conviction interval (CI) were calculated [31]. This was calculated as the difference between cases and control grouping means divided by the pooled SD. Interpretation of SMDs was based on previous outcome size (ES) guidelines: modest effect ≥ 0.2, medium consequence ≥ 0.5, large consequence ≥ 0.eight [32]. Effect sizes were considered statistically pregnant if the 95 % CI did not contain naught for the SMD. All data were analysed using the Comprehensive Meta-assay, version 2 [33]. When hateful and SD was not reported, the median and range were reported. Studies that met the inclusion criteria but did not report SD, or where the SD could not be obtained were excluded from meta-analysis (Boosted file 2: Table S2).

Results

Selection and characteristics of studies

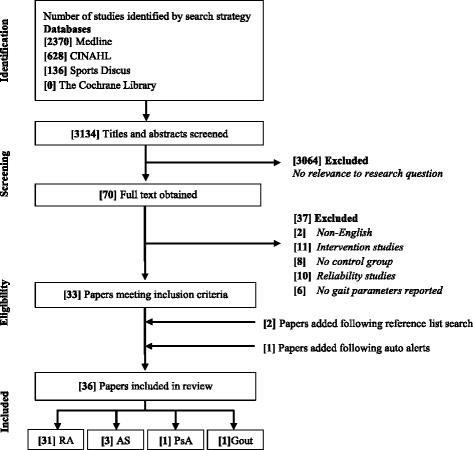

A total of 3134 citations were identified for screening with 36 articles being included for further analysis (Fig. 1). Thirty-one studies evaluated gait parameters in RA [seven, 8, 11, xiii–eighteen, 34–55], three in Equally [10, 56, 57] one in PsA [21] and i in gout [12]. Twenty-four studies examined spatiotemporal gait parameters, with nineteen in RA, two in Every bit, one PsA and gout (Additional file 3: Table S3). Twenty-one studies assessed kinematic parameters, with 17 in RA, three As and one in PsA (Additional file iv: Table S4). X studies examined kinetic parameters with eight in RA, one As and one in PsA (Additional file 5: Table S5). Xvi studies evaluated plantar pressure level parameters, with 15 in RA and 1 in gout (Boosted file half dozen: Table S6). 3 studies assessed all gait parameters (spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic and plantar pressures) in the population of interest [11, xiv, xv]. No studies reported gait characteristics in polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. The total number of participants was 2275; 1321 with IA and 954 controls. IA participants included 863 females and 312 males. The hateful (SD) age of IA cases and controls was 52.vi (9.3) and 47.8 (ix.2) years, respectively (Tabular array ane).

Menses of information through different stages of systematic review. RA = rheumatoid arthritis, AS = ankylosing spondylitis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis

Methodological quality of studies

Two reviewers (MC & KR) individually scored a full of 504 items and agreed on 480 items (95 %) with an inter-rater agreement of ƙ = 0.90 (p < 0.001). Six of the 36 articles were of high quality (quality score ≥ 12). The median (%) quality score of all articles was 10 (67 %), ranging between 20–87 % (Tabular array two). There was limited information on the methods of report recruitment across the majority of studies making information technology hard to assess the generalisability of study results. The bulk of studies investigating kinematic and kinetic parameters also reported small sample sizes.

Spatiotemporal gait parameters

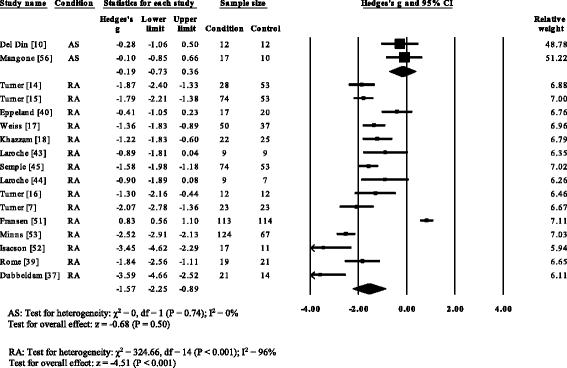

Fifteen RA [7, 14–xviii, 37, 39, twoscore, 44, 45, 51–54], one PsA [21] and i gout study [12] reported significant decreases in walking velocity. No significant differences in walking velocity were reported for AS [10, 56]. Overall pooled data (SMD, 95 % CI) (Fig. ii) for walking velocity, demonstrated a meaning decreased large effect size for RA (SMD −ane.55, −2.27 to −0.83) and a non-significant subtract for As (SMD −0.19, −0.73 to 0.36).

Wood plot of studies reporting walking velocity. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

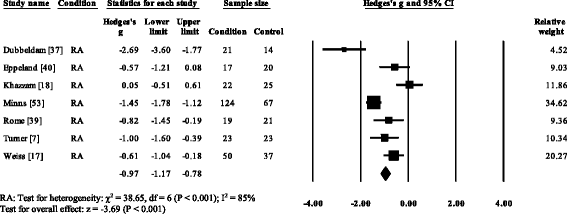

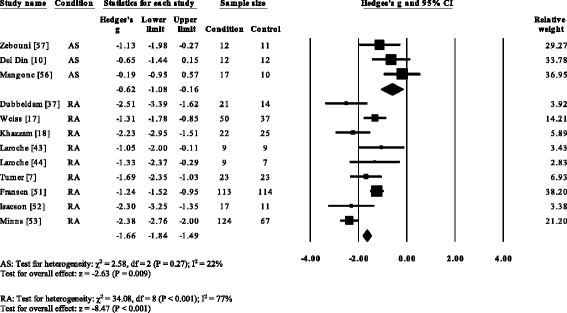

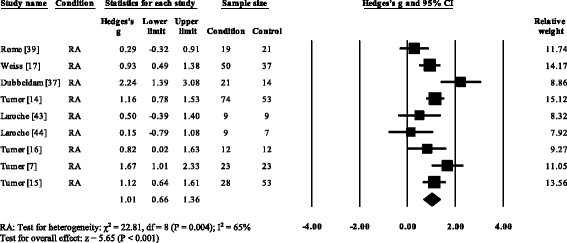

V RA studies [vii, 17, 37, 39, 53] and i gout (52) reported significant decreases in cadence. Cadence was not significantly decreased in AS [57]. Overall, pooled information for cadence in RA (Fig. three) showed a decreased but significant large effect size (SMD −0.97, −one.49 to −0.45). Nine RA studies [vii, 17, 18, 37, 44, 51–54], i AS [57] and one gout [12] reported pregnant decreases in stride length. Pooled data for stride length in RA (SMD −1.66, −i.84 to −i.49) and As (SMD −0.62, −1.08 to −0.27) were significantly decreased with a big effect size (Fig. iv). Viii RA studies [seven, 14–17, 37, 39, 51] and one gout study [12] reported significant increases in double back up. Pooled data for double back up in RA showed (Fig. 5) a significantly increased large result size (SMD 1.01, 0.66 to 1.36).

Forest plot of studies reporting cadence. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, conviction interval

Forest plot of studies reporting footstep length. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, conviction interval

Forest plot of studies reporting double support time. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Kinematic and kinetic gait parameters

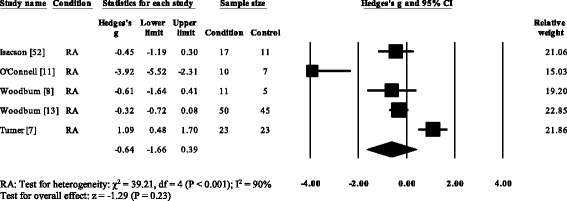

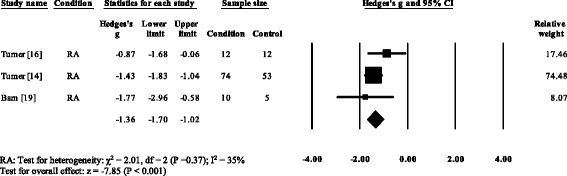

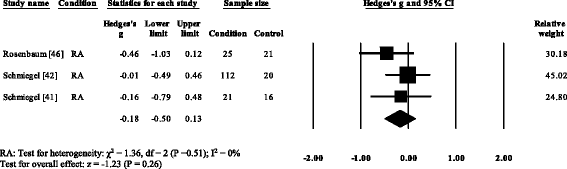

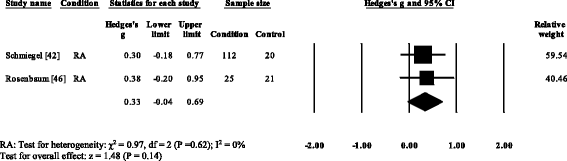

Five RA studies reported on the total ankle range of motion [vii, 8, eleven, 13, 52]. Iii studies reported no meaning differences [8, 13, 52], with one report reporting a significant increase [7] and one study reporting a pregnant decrease in the total ankle range of motion [11]. Results of the meta-analysis (Fig. 6) demonstrated that the overall effect size for total ankle range of move was not-meaning (SMD −0.64, −one.66 to 0.39). Ankle ability was reported in three RA [15, sixteen, 35] and one PsA written report [21]. All four studies reported pregnant reductions in ankle power. The overall consequence size for talocrural joint power in RA (Fig. 7) was significantly big (SMD −1.36, −1.seventy to −ane.02).

Forest plot of studies reporting ankle range of movement. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Forest plot of studies reporting ankle power. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, conviction interval

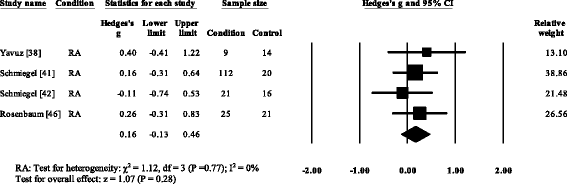

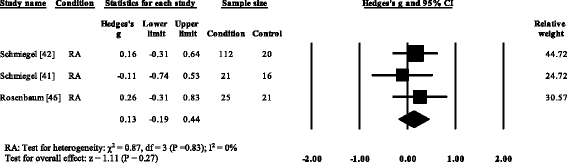

Peak plantar pressure gait parameters

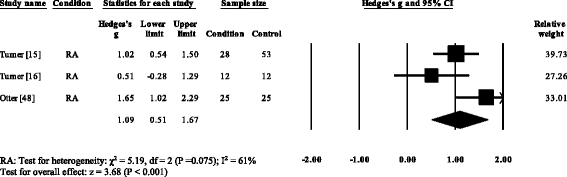

Three RA studies [fourteen, 16, 47, 48] reported significantly higher forefoot superlative plantar pressures in RA. Results from the meta-assay (Fig. eight) showed that the overall effect size for top plantar pressure to the forefoot was significantly large (SMD 1.09, 0.51 to 1.67). Pooled results in the RA studies demonstrated no meaning differences in peak plantar pressure for the rearfoot (Fig. 9), midfoot (Fig. x), first metatarsal (Fig. 11), iind metatarsal (Fig. 12) and the 3–vth metatarsal heads (Fig. thirteen). Hallux acme plantar pressure (Fig. 14) was reported to be significantly lower in gout [12].

Forest plot of studies reporting forefoot peak plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Forest plot of studies reporting rearfoot peak plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Forest plot of studies reporting midfoot elevation plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

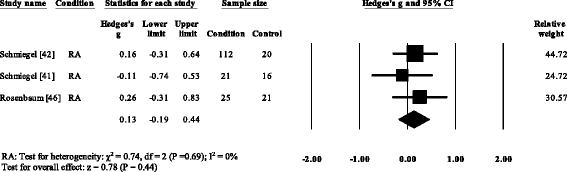

Woods plot of studies reporting 1st metatarsophalangeal height plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Forest plot of studies reporting twond metatarsophalangeal peak plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

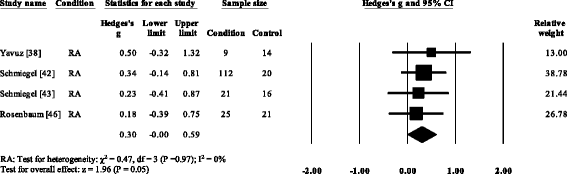

Wood plot of studies reporting 3rd to 5th metatarsophalangeal peak plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, conviction interval

Forest plot of studies reporting hallux elevation plantar pressure. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CI, confidence interval

Muscle activity

One RA study investigated muscle activity of the tibialis posterior muscle and reported increased muscle activity during the single back up stage of gait [35].

Give-and-take

This systematic review highlights significant differences in gait variables between people with IA and controls. The review found the majority of studies written report on RA with a limited number of studies on other IA weather. The review constitute similar findings to previous studies, that people with RA adopt an antalgic gait resulting from a hurting avoidance pattern that contributes to a subtract in walking velocity, cadence, increased double limb support time, and decreased ankle power with increased peak plantar pressures to the forefoot [eleven, 15, 17, 18]. Antalgic gait was also found in gout and AS suggesting that accommodation may occur due to the disease or a compensatory mechanism to accommodate for localised pes pain and deformity [14]. Gait adaptation in PsA may chronicle to entheseal foot pathologies and human foot hurting [9, 58]. Woodburn [21] postulated a stress shielding mechanism may be the commuter of gait accommodation with walking speeds decreased in endeavour to lower stress at the Achilles tendon. The review establish a reduction in elevation plantar pressure nether the first metatarsal head, suggesting that people with gout may employ a pain-avoidance strategy to reduce the pain associated with the structural joint damage of the beginning metatarsophalangeal joint.

The chief reward of three-dimensional (3D) motion analysis is that dynamic assessments of foot motility during functional activities, such as walking, tin can be performed [59]. Recent advances in motion capture technology afford improved spatial resolution and permit the definition of relatively modest segments in the foot [59]. In the concluding decade in that location has been an exponential growth in the utilize of 3D models to explicate gait strategies [sixty]. The evolution of detailed human foot models is beginning to quantify the kinematics and kinetics of the foot, still there are limitations for use in people with IA. Issues related to soft tissue artefacts and the validity of skin markers to track underlying skeletal segments remains problematic. Inaccurate identification of anatomical landmarks due to the presence of foot deformity in IA may affect the estimation, interpretation and reconstruction of articulation axis and ultimately the calculation of joint kinematics and kinetics [61]. The development of human foot models has besides increased the item and variety of 3D motion assay variables used to explicate gait strategies in people with IA. In comparing to spatiotemporal gait parameters and plantar pressure variables at that place appears to be no consensus every bit to the about important gait variables that relate to overall functional status.

This review has some limitations. There was a large variation in the disease activity, disease duration and level of deformities across all studies. Many studies used relatively pocket-sized samples that were underpowered and the heterogeneous nature of the IA population makes interpretation of the data difficult. A number of studies were included in the review but excluded from data pooling due to a lack of data reporting of standard deviations and mean values of gait parameters. Previous studies have described a broad range of methodologies to acquire and define gait parameters and this complicates the synthesis of information across different studies. The review was restricted to case-command studies and did non consider findings from intervention studies. We only analysed the human foot and ankle characteristics in IA, with no consideration given to information from the knee, hip and pelvis.

2 key pathways have been postulated to contribute to the evolution of pes hurting and deformity in IA: inflammatory and/or mechanical [59]. However, limited objective evidence exists to comprehensively examine inflammatory and mechanical markers in the context of foot pain and deformity beyond IA conditions. Given the express information across all IA conditions, future directions should include assay of musculus activity; this will provide information on the forces producing movements and patterns of muscle activation. Time to come research is required to understand the combined effects of spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic and plantar force per unit area touch on on pes function. This will let for relationships to be investigated across the differing gait parameters and may farther define the machinery of gait accommodation with IA atmospheric condition.

Conclusion

The advancement of 3D gait analysis has given a clearer insight into the complex interaction between the underlying mechanisms of inflammation and mechanical pathways that influence the evolution of foot bug in people with IA. The review identified 36 gait studies with the bulk of studies reporting gait adaptations in RA, simply limited prove relating to other IA conditions. Poor information reporting, small sample sizes and heterogeneity across IA weather condition limit the estimation of the findings. Hereafter studies should consider a standardised analytical approach to gait analysis that will enable comparisons across studies and provide clinicians and researchers with objective evidence of foot part in people with IA.

References

-

Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Brady TJ. A public health approach to addressing arthritis in older adults: the most common cause of inability. Am J Public Wellness. 2012;102(3):426–33.

-

Epstein FH, Harris Jr ED. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathophysiology and implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(eighteen):1277–89.

-

Frizziero A, Bonsangue Five, Trevisan Thousand, Ames PRJ, Masiero Due south. Pes tendinopathies in rheumatic diseases: etiopathogenesis, clinical manifestations and therapeutic options. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(5):547–55.

-

Reveille JD, Arnett FC. Spondyloarthritis: update on pathogenesis and management. Am J Med. 2005;118(half-dozen):592–603.

-

Richette P, Bardin T. Gout. Lancet. 2010;375:318–28.

-

Platto MJ, O'Connell PG, Hicks JE, Gerber LH. The relationship of pain and deformity of the rheumatoid foot to gait and an index of functional ambulation. J Rheumatol. 1991;xviii(ane):38–43.

-

Turner D, Woodburn J, Helliwell P, Cornwall M, Emery P. Foot planovalgus in RA: a descriptive and analytical study of foot office determined by gait analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2003;1(1):21–33.

-

Woodburn J, Nelson K, Siegel K, Kepple T, Gerber L. Multisegment pes motion during gait: proof of concept in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(x):1918–27.

-

Hyslop East, McInnes IB, Woodburn J, Turner DE. Human foot issues in psoriatic arthritis: high burden and low care provision. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):928.

-

Del Din S, Carraro E, Sawacha Z, Guiotto A, Bonaldo L, Masiero S, et al. Impaired gait in ankylosing spondylitis. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2011;49(7):801–9.

-

O'Connell PG, Lohmann Siegel One thousand, Kepple TM, Stanhope SJ, Gerber LH. Forefoot deformity, pain, and mobility in rheumatoid and nonarthritic subjects. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(ix):1681–half-dozen.

-

Rome K, Survepalli D, Sanders A, Lobo Grand, McQueen F, McNair P, et al. Functional and biomechanical characteristics of foot illness in chronic gout: A case-control study. Clin Biomech. 2011;26(i):90–four.

-

Woodburn J, Helliwell P, Barker Due south. Three-dimensional kinematics at the talocrural joint joint complex in rheumatoid arthritis patients with painful valgus deformity of the rearfoot. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(12):1406–12.

-

Turner D, Woodburn J. Characterising the clinical and biomechanical features of severely plain-featured feet in rheumatoid arthritis. Gait Posture. 2008;28(four):574–fourscore.

-

Turner DE, Helliwell PS, Siegel KL, Woodburn J. Biomechanics of the pes in rheumatoid arthritis: Identifying aberrant function and the factors associated with localised disease 'impact'. Clin Biomech. 2008;23(1):93–100.

-

Turner DE, Helliwell PS, Emery P, Woodburn J. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on foot office in the early stages of disease: a clinical case series. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:102–viii.

-

Weiss RJ, Wretenberg P, Stark A, Palmblad K, Larsson P, Gröndal L, et al. Gait blueprint in rheumatoid arthritis. Gait Posture. 2008;28(ii):229–34.

-

Khazzam 1000, Long JT, Marks RM, Harris GF. Kinematic changes of the human foot and ankle in patients with systemic rheumatoid arthritis and forefoot deformity. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(three):319–29.

-

Barn R, Turner DE, Rafferty D, Sturrock RD, Woodburn J. Tibialis posterior tenosynovitis and associated pes plano valgus in rheumatoid arthritis: EMG, multi‐segment foot kinematics and ultrasound features. Arthritis Intendance Res. 2012;65(4):495–502.

-

Broström EW, Esbjörnsson A-C, von Heideken J, Iversen Doctor. Gait deviations in individuals with inflammatory joint diseases and osteoarthritis and the usage of iii-dimensional gait assay. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(3):409–22.

-

Woodburn J, Hyslop E, Barn R, McInnes I, Turner D. Achilles tendon biomechanics in psoriatic arthritis patients with ultrasound proven enthesitis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2013;00:i–iv.

-

Salvarani C, Cantini F, Macchioni P, Olivieri I, Niccoli 50, Padula A, et al. Distal musculoskeletal manifestations in polymyalgia rheumatica: a prospective followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(7):1221–six.

-

Hietaharju A, Jääskeläinen Southward, Kalimo H, Hietarinta M. Peripheral neuromuscular manifestations in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Muscle Nervus. 1993;16(11):1204–12.

-

Williams A, Crofts Yard, Teh L. 'Focus on feet'–the furnishings of systemic lupus erythematosus: a narrative review of the literature. Lupus. 2013;22(10):1017–23.

-

Baan H, Dubbeldam R, Nene AV, van de Laar MAFJ. Gait analysis of the lower limb in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(vi):768–88. e768.

-

Downs South, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and not-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

-

Meyer S, Karttunen AH, Thijs V, Feys H, Verheyden G. How practice somatosensory deficits in the arm and hand relate to upper limb harm, action, and participation problems later stroke? A systematic review. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1220–31.

-

Liu Y, Davari-Farid S, Arora P, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. Early versus belatedly initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically Sick patients with astute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-assay. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(3):557–63.

-

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557.

-

Deeks JJ, Higgins J, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. 2008. p. 243–96.

-

Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Drinking glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat. 1981;6(2):107–28.

-

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(i):155–ix.

-

Borenstein M, Hedges Fifty, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive meta-analysis version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005. p. 104.

-

Woodburn J, Turner D, Helliwell P, Barker S. A preliminary study determining the feasibility of electromagnetic tracking for kinematics at the ankle joint complex. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38(12):1260–8.

-

Barn R, Turner DE, Rafferty D, Sturrock RD, Woodburn J. Tibialis posterior tenosynovitis and associated pes Plano valgus in rheumatoid arthritis: electromyography, multisegment pes kinematics, and ultrasound features. Arthritis Care & Res. 2013;65(iv):495–502.

-

Bowen CJ, Culliford D, Allen R, Beacroft J, Gay A, Hooper 50, et al. Forefoot pathology in rheumatoid arthritis identified with ultrasound may not localise to areas of highest pressure: cohort observations at baseline and twelve months. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4(1):25.

-

Dubbeldam R, Nene AV, Buurke JH, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Baan H, Drossaers-Bakker KW, et al. Foot and ankle articulation kinematics in rheumatoid arthritis cannot only be explained by alteration in walking speed. Gait Posture. 2011;33(three):390–5.

-

Yavuz 1000, Husni E, Botek G, Davis BL. Plantar shear stress distribution in patients with rheumatoid arthritis relevance to pes pain. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(4):265–nine.

-

Rome K, Dixon J, Greyness Chiliad, Woodley R. Evaluation of static and dynamic postural stability in established rheumatoid arthritis: exploratory study. Clin Biomech. 2009;24(6):524–6.

-

Eppeland Due south, Myklebust G, Hodt-Billington C, Moe-Nilssen R. Gait patterns in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis cannot be explained by reduced speed alone. Gait Posture. 2009;29(3):499–503.

-

Schmiegel A, Vieth V, Gaubitz M, Rosenbaum D. Pedography and radiographic imaging for the detection of foot deformities in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Biomech. 2008;23(5):648–52.

-

Schmiegel A, Rosenbaum D, Schorat A, Hilker A, Gaubitz Chiliad. Assessment of foot harm in rheumatoid arthritis patients by dynamic pedobarography. Gait Posture. 2008;27(1):110–iv.

-

Laroche D, Ornetti P, Thomas East, Ballay Y, Maillefert JF, Pozzo T. Kinematic accommodation of locomotor pattern in rheumatoid arthritis patients with forefoot harm. Exp Encephalon Res. 2007;176(1):85–97.

-

Laroche D, Pozzo T, Ornetti P, Tavernier C, Maillefert JF. Furnishings of loss of metatarsophalangeal articulation mobility on gait in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(4):435–forty.

-

Semple R, Turner DE, Helliwell PS, Woodburn J. Regionalised centre of pressure analysis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Biomech. 2007;22(ane):127–nine.

-

Rosenbaum D, Schmiegel A, Meermeier G, Gaubitz M. Plantar sensitivity, foot loading and walking pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(2):212–4.

-

Tuna H, Birtane G, Taştekin North, Kokino S. Pedobarography and its relation to radiologic erosion scores in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2005;26(i):42–7.

-

Otter SJ, Bowen CJ, Young AK. Forefoot plantar pressures in rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004;94(3):255–60.

-

Woodburn J, Helliwell PS. Relation betwixt heel position and the distribution of forefoot plantar pressures and skin callosities in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(11):806–10.

-

Siegel KL, Kepple TM, O'Connell PG, Gerber LH, Stanhope SJ. A technique to evaluate foot part during the stance stage of gait. Foot Talocrural joint Int. 1995;sixteen(12):764–70.

-

Fransen G, Heussler J, Margiotta East, Edmonds J. Quantitative gait assay—comparison of rheumatoid arthritic and non-arthritic subjects. Aust J Physiother. 1994;40(3):191–ix.

-

Isacson J, Broström LÅ. Gait in rheumatoid arthritis: an electrogoniometric investigation. J Biomech. 1988;21(6):451–3. 455–457.

-

Minns R, Craxford Advertizement. Pressure under the forefoot in rheumatoid arthritis a comparing of static and dynamic methods of assessment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;187:235.

-

Simkin A. The dynamic vertical strength distribution during level walking under normal and rheumatic feet. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1981;20(2):88–97.

-

Stauffer RN, Chao EY, Györy AN. Biomechanical gait analysis of the diseased knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;126:246–55.

-

Mangone Thousand, Scettri P, Paoloni M, Procaccianti R, Spadaro A, Santilli Five. Pelvis-shoulder coordination during level walking in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Gait Posture. 2011;34(1):1–5.

-

Zebouni L, Helliwell P, Howe A, Wright V. Gait assay in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51(vii):898–9.

-

Hyslop E, Woodburn J, McInnes I, Semple R, Newcombe 50, Hendry G, et al. A reliability study of biomechanical foot role in psoriatic arthritis based on a novel multi-segmented foot model. Gait Posture. 2010;32(4):619–26.

-

Rao S. Quantifying pes office in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis: recent advances and clinical implications. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(4):493–iv.

-

Deschamps K, Staes F, Roosen P, Nobels F, Desloovere K, Bruyninckx H, et al. Body of bear witness supporting the clinical use of 3D multisegment foot models: A systematic review. Gait Posture. 2011;33(3):338–49.

-

Della Croce U, Leardini A, Chiari L, Cappozzo A. Human being move analysis using stereophotogrammetry: Function four: assessment of anatomical landmark misplacement and its effects on articulation kinematics. Gait Posture. 2005;21(2):226–37.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Arthritis New Zealand.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MC proposed the study protocol, which was elaborated and specified by KR, ND & PP. MC and KR screened all the references and extracted the data. MB served equally arbitrator in case of discrepancies during extraction. PP supported the data extraction procedure. All authors interpreted the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Boosted file i:

Table S1. Clarification of search strategy. Details of specific search terms used and the social club in which the search tool place.

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Excluded studies. Details of the publications excluded, the reason for exclusion and the reference list of the excluded studies.

Additional file three:

Table S3. Spatiotemporal gait analysis parameters acquired past included studies. Details of the data acquisition method and the specific spatiotemporal parameters that were measured by studies assessing spatiotemporal gait parameters.

Boosted file iv:

Table S4. Kinematic gait parameters measured and methods of data acquisition. Details of the specific kinematic parameters, measured the biomechanical model used to determine kinematic parameters.

Additional file 5:

Table S5. Kinetic gait assay parameters acquired by included studies. Details of kinetic gait parameters measured.

Additional file half dozen:

Table S6. Plantar pressure parameters acquired by included studies. Details of the specific regions of the foot where plantar pressure was measured and the method past which plantar pressure was caused.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cipher/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Carroll, Grand., Parmar, P., Dalbeth, N. et al. Gait characteristics associated with the human foot and ankle in inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 134 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0596-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0596-0

Keywords

- Gait

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Gout

Source: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-015-0596-0

0 Response to "American Family Physician, 2015 Antalgic Gait Flow Sheet"

Post a Comment